If you don’t read the newspaper, you’re uninformed. If you read the newspaper, you’re mis-informed.

― Mark Twain

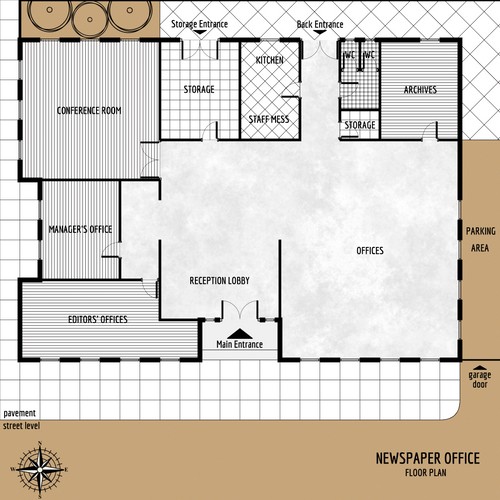

Welcome to this Small Town Newspaper Office! The investigators will surely find a plethora of information in this office. Here you can find some journalists or the editor that may remember that old murder that remain unsolved for many years.

With this map you get:

- grid & gridless variations

- PNG files, low (70 PPI) & high (140 PPI) resolutions

- day & night variations

- vintage, modern, abandoned & splatter variations

- floor plan

- dd2vtt files for FoundryVTT & Roll20

- High-resolution WebP files

- A monthly Foundry Module with all the maps of the month personally curated by me with walls, windows, doors, lights, and more.